What is a PhD student in skin cancer doing at the Section of Forensic Genetics?

When skin cancer is suspected

Today, most commonly biopsies are used to discard or confirm suspicions of skin cancer. In the biopsy procedure, the doctor applies local anesthetics where the sign of skin cancer has appeared on the patient’s skin and removes a small part of the top layer of skin, and after 1-2 weeks the lab provides an answer to the suspicion.

Tape and scanners are not office supplies

The biopsy procedure has a relatively long processing time and may cause a bit of discomfort for the patient, so one of our missions is to find new ways that are faster and more pleasant for the patient when doctors investigate possible cases of skin cancer. For this purpose, Kevin is investigating two new non-invasive methods in his PhD project: tape and scan. And though it may sound as office supplies, they are actually advanced methods for mapping biologic matter.

Forensic geneticists use tape to collect biologic trace

Forensic geneticists are constantly working on mapping DNA and RNA from continuously smaller samples of biologic material found at crime scenes to identify the donors of the material. The samples can be collected with tape. Using the tape on human skin, the tape only removes dead skin cells from the top layer of the skin fast and painlessly, and we would like to know whether these small amounts of RNA collected with tape also can be used to identify or characterize skin cancer. So, we have joined forces with the Section of Forensic Genetics, and that’s why Kevin has spent time at their premises. For two weeks he has been working closely with Associate Professor Jeppe Dyrberg Andersen to summarize a research project which will be the first of its kind in Europe.

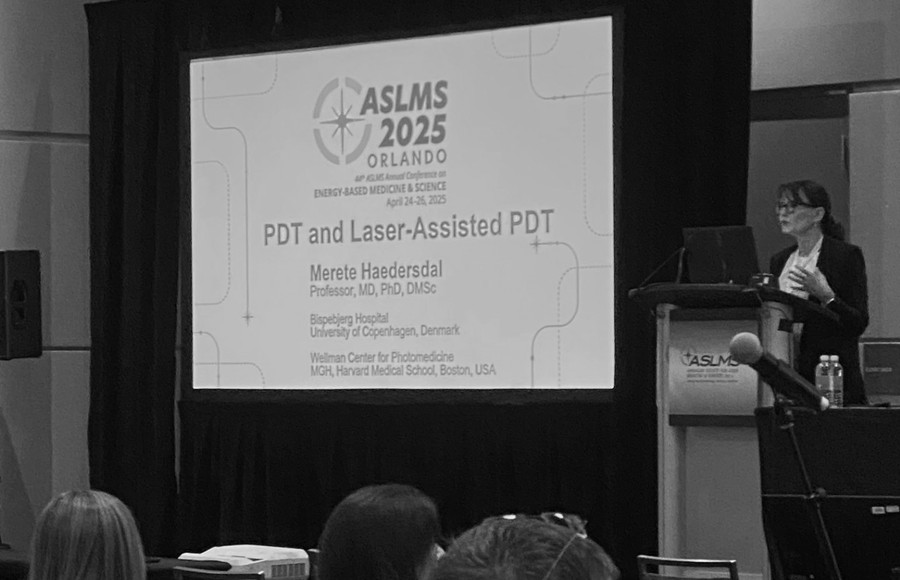

Bispebjerg Hospital got the first LC-OCT scanner in the Nordic countries

Beside the tape method, Kevin is looking into the use of scanners for diagnosing skin cancer. The scanner currently tested is a LC-OCT scanner or a Line-Field Confocal Optical Coherence Tomography scanner as the entirety of the name is. There are only a few LC-OCT scanners worldwide, and Bispebjerg Hospital was the first hospital in the Nordic countries to get one. During the scan, the doctor moves a handheld scanning device across the surface of the patient’s skin where the doctor suspects there might be skin cancer. The scanner makes a series of recordings of the skin and presents these as images the doctor can analyze immediately and provide an answer to the suspicion right away. And where the biopsy can only provide an answer to a small sample of the skin, the scan can cover larger areas. This makes the scan faster, more pleasant and provides a broader foundation for medical decisions.

Research requires time

When you are among the first in the world to tread new ground, you usually do not have a detailed map to go by. This is also the case when you are among the first in the world to use a new scanner. There is manual on how to operate the scanner but not on how to analyze the scanning images. In order to define how to correctly interpret the images, since 2021 in a transnational research environment, Kevin has mapped how to use the technique in various scenarios, how to interpret the images, what to look for and the complexity of the images. This brings us closer to implementing the technique in Danish skin clinics and the aim of offering patients a seamless process by minimizing the need for biopsies and making diagnosing skin cancer faster and easier.

Can we combine the two methods and plan treatment of skin cancer better?

Another topic we would like to explore is whether combining the two methods, tape and scan, can provide a better foundation for the doctor to plan the treatment for the individual patient. Scanning provides a fast answer and for a larger part of the skin than a biopsy can, and the tape analysis offers more in-depth knowledge of the patient scenario. Using this collective data, it might be possible to plan individual treatment without taking biopsies at all.

Next step in the project is to get approval from the Danish Research Ethics Committees for the tape investigation.

Project supervision

Provided by Danish Research Center for Skin Cancer and led and sponsored by Professor, Chief Physician Merete Hædersdal (MD, DMSc, PhD ), Bispebjerg Hospital.

Assisted by Danish Research Center for Skin Cancer, Senior Researcher Peter Philipsen (PhD, MSc Electrical Engineer), Bispebjerg Hospital.

In collaboration with Section of Forensic Genetics, Department of Forensic Medicine, University of Copenhagen, Associated Professor Jeppe Dyrberg Andersen (MSc in Bio Technology, PhD).

Image from Bispebjerg Hospital.